Dogs, cats and swine flu’s promiscuity

reprinted from Science Blog’s Effect Measure

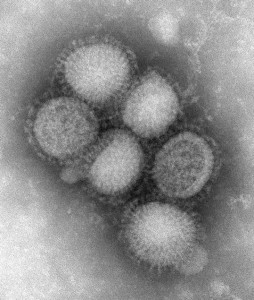

Swine flu started in pigs (although we don’t know exactly when or where), adapted to and passed to humans who returned the favor and passed it back to pig herds. Then we heard that turkeys in Chile had contracted the virus, followed by ferrets and a house cat. We can infect animals cross species with flu in the laboratory, but all of these are cases acquired in the natural world by animals interacting with humans. Once cats were on the menu, the next question was dogs, another population “companion animal” (aka, pet) in the US and Western Europe (and literally a menu item in many parts of Asia). In recent years there have been periodic outbreaks of “dog flu,” an H3N8 subtype that didn’t seem to infect humans but produced “kennel cough” like symptoms in dogs. Now we get reports out of China that the family dog can also be infected with swine flu — by us:

Swine flu started in pigs (although we don’t know exactly when or where), adapted to and passed to humans who returned the favor and passed it back to pig herds. Then we heard that turkeys in Chile had contracted the virus, followed by ferrets and a house cat. We can infect animals cross species with flu in the laboratory, but all of these are cases acquired in the natural world by animals interacting with humans. Once cats were on the menu, the next question was dogs, another population “companion animal” (aka, pet) in the US and Western Europe (and literally a menu item in many parts of Asia). In recent years there have been periodic outbreaks of “dog flu,” an H3N8 subtype that didn’t seem to infect humans but produced “kennel cough” like symptoms in dogs. Now we get reports out of China that the family dog can also be infected with swine flu — by us:

Two dogs in Beijing have tested positive for swine flu in the second case of animals catching the disease in China along with pigs in the northeast, Chinese media said Sunday.

The A(H1N1) virus detected in the dogs was 99 percent identical to the one circulating in humans, the state-run Beijing Times reported, quoting China’s agriculture ministry.The news comes 10 days after four pigs in China’s Heilongjiang province were diagnosed with the virus, which specialists said might have been caught from humans, the report said.

Countries including the United States, Canada and Chile have already reported cases of animals being infected with the A(H1N1) virus.

A cat in the US state of Iowa was diagnosed with swine flu at the beginning of the month in the first known case in the world of the new pandemic strain spreading to the feline population. (iafrica.com; h/t Chen Qui)

The Chinese news service Xinhua is reporting that the virus was found in 2 samples of 52 taken from sick dogs at the China Agricultural University College of Veterinary Medicine and genetic analysis showed it to be 99% homologous to virus from cases of human swine flu.

What strikes us about this is not the danger to dogs specifically but the amazing promiscuity this virus is showing. We have always thought of influenza virus subtype strains to be relatively host species specific, although exceptions do exist. Humans occasionally get the devasting (to us) H5N1 bird flu, which can also infect cats, ferrets and a few other animals, but all rarely. This virus doesn’t seem to care if you are a human, pig, turkey, dog, cat, ferret or who knows what else. Maybe that’s too strong, because while all those infections have been reported we still don’t know how easy it is to transmit. But nothing so far suggests it’s extremely rare. On the contrary, the evidence suggests if we start looking for infections in other species we will start to find them.

I don’t see why we should be thinking only of mammals and birds. Could the influenza virus also infect insects or reptiles or amphibians? (NB: a new vaccine production method in caterpillar cells doesn’t use the flu virus but an insect virus with the gene for the flu HA protein spliced into it; our post here). Maybe there’s a good biological barrier to that but if there is, I don’t know what it is and I don’t think we’ve done much looking outside of birds, humans and pigs.

The species promiscuity of this virus raises still another issue. Influenza viruses not only have species preferences but tissue preferences (called tropisms). Rabies virus infects nervous tissue but not kidneys while flu mainly (although not exclusively) likes cells in the respiratory tract. But if this virus is so indifferent to what species it is infecting, might it not also develop a wider palette of tissue tropisms? Nothing we see in the genetic sequences predicts the striking host non-specificity or what’s allowing it and we are still pretty vague on the distribution of viral receptors in different body tissues, assuming we even know how to characterize those receptors (the conventional story of the 2,3 versus 2,6 sialic acid linkages seems now to be much more complicated; see our posts here and here for more about this).

The dog and cat story may mean a lot more than our pets are at risk. Right now these are just questions. How hard it will be to get the answers and how long it will take is anyone’s guess.

What do you think?